From Jamie Oliver’s ‘chips and cheese’ and a ‘massive fucking TV’ comments, to the sneering ‘Benefits Street’, absent from the discourse on Britain’s poor is discussion of the material processes that cause poverty. Instead we see a committed Othering of poor people; a belief in social pathologies and moral inferiority. In this blog, Stephen Crossley author of In Their Place, explores this manipulation of public discourse; examining how often ethnographic research, and the institutions that fund it, often reinforce these stigmatising narratives through methodological approaches and practices.

From Jamie Oliver’s ‘chips and cheese’ and a ‘massive fucking TV’ comments, to the sneering ‘Benefits Street’, absent from the discourse on Britain’s poor is discussion of the material processes that cause poverty. Instead we see a committed Othering of poor people; a belief in social pathologies and moral inferiority. In this blog, Stephen Crossley author of In Their Place, explores this manipulation of public discourse; examining how often ethnographic research, and the institutions that fund it, often reinforce these stigmatising narratives through methodological approaches and practices.

In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty explores how spaces of poverty and representations of disadvantaged people are used by politicians, the media, policy makers and academics to ensure a gap in inequality remains and that everyone knows where the poor belong.

————————-

Members of the public could be forgiven for barely batting an eyelid when David Cameron announced in 2014 that he was going to ‘blitz’ poverty by knocking down what he referred to as ‘sink estates’. Cameron argued that it wasn’t a coincidence that people who participated in the 2011 riots came ‘overwhelmingly’ from post-war housing estates and suggested that some such estates were ‘actually entrenching poverty in Britain – isolating and entrapping many of our families and communities’. There is, of course a long history of politicians and other prominent individuals – journalists, social reformers, media personalities, authors – of conflating places where poor people live, with locales that produce both poverty, and an assortment of other, often tenuously connected, ‘social problems’.

William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, compared the East End of London with outposts of Empire and, in 1890, rhetorically asked:

‘As there is a darkest Africa, is there not also a darkest England? Civilisation, which can breed its own barbarians, does it not also breed its own pygmies?’

More recently, Iain Duncan Smith famously ‘discovered’ his ‘passion’ for social justice (one is left wondering how he had previously missed it…) following visits to Easterhouse in Glasgow. His discovery led him to establish the Centre for Social Justice think-tank and staff it with ‘lackey intellectuals’ whose ‘research’ identified five ‘pathways to poverty’, which relied on and promoted behaviourist explanations for poverty. Jamie Oliver has proffered his own helpful contributions to debates about poverty in the UK at the current time, arguing that an episode of one of his television shows which featured a child eating ‘chips and cheese out of Styrofoam containers, and behind them is a massive fucking TV’ showed that poverty in modern-day Britain ‘just didn’t weigh up’.

One might hope, if not expect, academics and academic institutions, supposedly capable of and supporting and advancing independent and critical thought, to robustly challenge such stereotypes. Alas, divergence from such lazy, stigmatising portrayals of disadvantaged neighbourhoods can also be found within the walls of academia. Tom Slater has powerfully argued that the ‘cottage industry’ of ‘neighbourhood effects’ research that focuses on how where you live affects your life chances, is deployed as ‘an instrument of accusation, a veiled form of class antagonism that conveniently has no place for any concern over what happens outside the very neighbourhoods under scrutiny.’ One university that I have connections with has produced a risk assessment that attempts to address the ‘increased hazards of testing in socially disadvantaged areas’. Potential researchers are encouraged to ‘investigate the area in which they’re planning on working in advance’ and ensure they are ‘aware of any social or cultural tensions in the area’. They are told to study a map of the area before conducting the research, and to check the location of areas that ‘might form the basis of obtaining assistance if required’. Further information is provided on personal safety with researchers reminded to ‘carry valuables in an unobtrusive and secure manner’, ‘consider safe places to park’ and, incredibly, ‘consider breaking routine so your timings vary’ if travelling to the neighbourhood on multiple days. This is not to undermine the need for lone workers to feel safe when carrying out their work and for appropriate mechanisms to be put in place to ensure their safety as far as possible. A generic risk assessment for carrying out research ‘off-site’ would be a useful resource for researchers about to embark on a study. The specific reference to ‘research carried out in a socially disadvantaged neighbourhood’, however, gives the game away. There is no such risk assessment for carrying out research in an ‘affluent neighbourhood’ or a ‘socially advantaged neighbourhood’ at the same institution. The insinuation is that poorer areas are more threatening and dangerous areas. In writing about the idea of disadvantaged neighbourhoods as ‘dreadful enclosures’ in 1977, the sociologist E.V. Walter wrote:

‘Certain milieu gather reputations for moral inferiority, squalor, violence, and social pathology, and consequently they objectify the fantasy of the dreadful enclosure … According to the stereotype, housing projects are loci in which sick and dangerous people drift together in a kind of behavioural sink, producing urban capsules of pathology so highly concentrated that the ordinary resources of the body social cannot control them.’[1]

Disadvantaged and marginalised populations have often been the subjects of a variety of social research from different disciplinary backgrounds. Researchers can gain credit, or symbolic capital, for carrying out research in such areas and with groups of people  others deem to be ‘hard to reach’, dangerous or threatening. For example, the American sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh, who recently took up a position at Facebook, wrote a book about how he was ‘gang leader for a day’ during ethnographic research in a housing project in Chicago. Simon Harding, a criminologist in the UK has published a book on status or ‘weapon dogs’ and another on street gangs in London, in which he describes gang members as players of the game in ‘the casino of life’. Sociologists in the UK who debunked the idea of households where ‘three generations have never worked’ highlighted the almost mythical status of such households amongst politicians, policy-makers, practitioners and members of the public, by likening their research to ‘hunting yetis’. Interest in disadvantaged groups has even led to an emerging literature on ‘over-researched communities’, with some young people in Kings Cross apparently confident in asking researchers working in their neighbourhood about their choice of methodology and ethical approval processes.

others deem to be ‘hard to reach’, dangerous or threatening. For example, the American sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh, who recently took up a position at Facebook, wrote a book about how he was ‘gang leader for a day’ during ethnographic research in a housing project in Chicago. Simon Harding, a criminologist in the UK has published a book on status or ‘weapon dogs’ and another on street gangs in London, in which he describes gang members as players of the game in ‘the casino of life’. Sociologists in the UK who debunked the idea of households where ‘three generations have never worked’ highlighted the almost mythical status of such households amongst politicians, policy-makers, practitioners and members of the public, by likening their research to ‘hunting yetis’. Interest in disadvantaged groups has even led to an emerging literature on ‘over-researched communities’, with some young people in Kings Cross apparently confident in asking researchers working in their neighbourhood about their choice of methodology and ethical approval processes.

And yet, going to see things close-up and first hand, does not necessarily lead to greater clarity of though or greater insight. The influential French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that:

‘The perfectly commendable wish to go see things in person, close up, sometimes leads people to search for the explanatory principles of observed realities where they are not to be found (not all of them, in any case), namely at the site of observation itself. The truth about what happens in the ‘problem suburbs’ certainly does not lie in these usually forgotten sites that leap into the headlines from time to time. The true object of analysis, which must be constructed against appearances and against all those who do no more than endorse those appearances, is the social (or more precisely political) construction of reality as it appears, to intuition, and of its journalistic, bureaucratic and political representations, which help to produce effects that are indeed real, beginning with the political world, where they structure discussion.’[2]

This is not to criticise the work of all researchers or academics who carry out ethnographic, or indeed other forms of research with marginalised groups or in/on disadvantaged communities and neighbourhoods. For example, Kayleigh Garthwaite spent a year volunteering in a foodbank in order to understand the issues and processes which led people to use foodbanks, in the process highlighting the political, structural and systemic causes of increased foodbank use in the UK. Lisa McKenzie has highlighted how residents of St. Ann’s in Nottingham experienced austerity and increasing class inequality. Researchers such as Rob Macdonald and Tracy Shildrick have documented the myriad effects of deindustrialisation in Teesside, expounding the difficult youth transitions to adulthood at a time of chastening political attitudes towards young people, and when the local labour market offers only low-paid precarious employment. These are all research studies of individuals and groups living in impoverished areas, but with one eye (at least) on the wider social and structural determinants of the lives of the research participants. In a similar vein, contributors to the recently published book The Violence of Austerity highlight the effects of austerity driven cuts and ‘reforms’ on different already structurally disadvantaged groups.

transitions to adulthood at a time of chastening political attitudes towards young people, and when the local labour market offers only low-paid precarious employment. These are all research studies of individuals and groups living in impoverished areas, but with one eye (at least) on the wider social and structural determinants of the lives of the research participants. In a similar vein, contributors to the recently published book The Violence of Austerity highlight the effects of austerity driven cuts and ‘reforms’ on different already structurally disadvantaged groups.

How disadvantaged and impoverished neighbourhoods, and the people that reside them, are depicted in research depends very much on how they are perceived in the first place. Martin Nicolaus, put it succinctly when he railed against ‘fat-cat sociologists’ who operated with their eyes trained downwards and their palms turned upwards, stating that ‘it all depends on where you look from, where you stand’. Research that views, or accepts the dominant political narrative that ‘socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods’ are threatening places, or a ‘problem’ that can best be understood by examining ‘neighbourhood effects’ or close-up research does nothing more than legitimise the stigmatising narratives about working class neighbourhoods or social housing estates. On the other hand, research that attempts to highlight the impact on poor neighbourhoods of political decisions made by powerful people living very different lives in very different neighbourhoods can help to reveal to reveal the impact of such decisions on communities across the country. Nicolaus, however, went further. He argued for a ‘reversal of the machinery’ and asked:

‘What if the habits, problems, secrets, and unconscious motivations of the wealthy and powerful were daily scrutinised by a thousand systematic researchers, were hourly pried into, analysed and cross-referenced; were tabulated and published in a hundred inexpensive mass-circulation journals and written so that even the fifteen-year-old high-school drop-out could understand them and predict the actions of his landlord to manipulate and control him?’[3]

If we want to truly understand how and why poverty affects some places more than others, we need to be turning our attentions to what might be termed ‘advantaged neighbourhoods’ and the daily lives of those that frequent the ‘corridors of power’. Decisions about resources and services that could be made available to neighbourhoods  and their residents are often taken hundreds of miles away, perhaps by people whose only experience or knowledge of poverty might have been gleaned from a carefully managed day trip or two. It is worth remembering that few, if any, of the politicians who voted through, or abstained during, the welfare reforms introduced in the UK since 2010, were going to be substantially affected by them, or could imagine what they might mean to many families already living on low incomes across the country. Numerous researchers have demonstrated various ‘Westminster effects’ on disadvantaged neighbourhoods by highlighting how the government’s recent welfare reforms have had disproportionately greater impact upon poorer areas. Whilst it is vital to acknowledge that where people live can affect their lives, a compelling case can and should be made that the strongest effects exerted on residents of impoverished neighbourhoods often emanate from the words and actions of politicians in Westminster, rather than the allegedly ‘mean streets’ of social housing estates.

and their residents are often taken hundreds of miles away, perhaps by people whose only experience or knowledge of poverty might have been gleaned from a carefully managed day trip or two. It is worth remembering that few, if any, of the politicians who voted through, or abstained during, the welfare reforms introduced in the UK since 2010, were going to be substantially affected by them, or could imagine what they might mean to many families already living on low incomes across the country. Numerous researchers have demonstrated various ‘Westminster effects’ on disadvantaged neighbourhoods by highlighting how the government’s recent welfare reforms have had disproportionately greater impact upon poorer areas. Whilst it is vital to acknowledge that where people live can affect their lives, a compelling case can and should be made that the strongest effects exerted on residents of impoverished neighbourhoods often emanate from the words and actions of politicians in Westminster, rather than the allegedly ‘mean streets’ of social housing estates.

———————

Stephen Crossley is Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at Northumbria University. He previously worked on a regional child poverty project in the North East of England and has also worked in local government and with local voluntary sector organisations in neighbourhood youth work and community development roles.

———————

In Their Place: The Imagined Geographies of Poverty by Stephen Crossley is available from Pluto Press.

———————

[1] E.V. Walter, ‘Dreadful Enclosures: Detoxifying and Urban Myth’, European Journal of Sociology 18/1 (1977): 150-159, quote from p. 154.

[2] P. Bourdieu et al., The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999), p. 181.

[3] M. Nicolaus, ‘Fat-cat Sociology: Remarks at the American Sociology Association Convention’, 1968 (available at: http://www.colorado.edu/Sociology/gimenez/fatcat.html, accessed 1 December 2016).

globalisation – and the massive leaps achieved in the fields of mass transport, communications, technology – have rendered individual states increasingly powerless vis-à-vis the forces of the market. The internationalisation of finance and the growing importance of multinational corporations have eroded the ability of individual states to autonomously pursue social and economic policies – especially of the progressive kind – and to deliver prosperity to their peoples. Financial markets and mega-corporations today wield more power than governments – and can easily bring these to their knees. This means that our only hope of tackling the cross-border challenges of modernity, of taming the power of global financial and corporate leviathans, and of achieving any meaningful change, is for countries to ‘pool’ their sovereignty together and transfer it to supranational institutions (such as the European Union) that are large and powerful enough to have their voices heard, thus regaining at the supranational level the sovereignty that has been lost at the national level. In other words, to preserve their ‘real’ sovereignty, states need to limit their formal sovereignty.

globalisation – and the massive leaps achieved in the fields of mass transport, communications, technology – have rendered individual states increasingly powerless vis-à-vis the forces of the market. The internationalisation of finance and the growing importance of multinational corporations have eroded the ability of individual states to autonomously pursue social and economic policies – especially of the progressive kind – and to deliver prosperity to their peoples. Financial markets and mega-corporations today wield more power than governments – and can easily bring these to their knees. This means that our only hope of tackling the cross-border challenges of modernity, of taming the power of global financial and corporate leviathans, and of achieving any meaningful change, is for countries to ‘pool’ their sovereignty together and transfer it to supranational institutions (such as the European Union) that are large and powerful enough to have their voices heard, thus regaining at the supranational level the sovereignty that has been lost at the national level. In other words, to preserve their ‘real’ sovereignty, states need to limit their formal sovereignty.

From Jamie Oliver’s ‘chips and cheese’ and a ‘massive fucking TV’ comments, to the sneering ‘Benefits Street’, absent from the discourse on Britain’s poor is discussion of the material processes that cause poverty. Instead we see a committed Othering of poor people; a belief in social pathologies and moral inferiority. In this blog, Stephen Crossley author of

From Jamie Oliver’s ‘chips and cheese’ and a ‘massive fucking TV’ comments, to the sneering ‘Benefits Street’, absent from the discourse on Britain’s poor is discussion of the material processes that cause poverty. Instead we see a committed Othering of poor people; a belief in social pathologies and moral inferiority. In this blog, Stephen Crossley author of

others deem to be ‘hard to reach’, dangerous or threatening. For example, the American sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh, who recently took up a position at Facebook, wrote a book about how he was ‘gang leader for a day’ during ethnographic research in a housing project in Chicago. Simon Harding, a criminologist in the UK has published a book on status or ‘weapon dogs’ and another on street gangs in London, in which he describes gang members as players of the game in ‘the casino of life’. Sociologists in the UK who debunked the idea of households where ‘three generations have never worked’ highlighted the almost mythical status of such households amongst politicians, policy-makers, practitioners and members of the public, by likening their research to ‘hunting yetis’. Interest in disadvantaged groups has even led to an emerging literature on ‘over-researched communities’, with some young people in Kings Cross apparently confident in asking researchers working in their neighbourhood about their choice of methodology and ethical approval processes.

others deem to be ‘hard to reach’, dangerous or threatening. For example, the American sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh, who recently took up a position at Facebook, wrote a book about how he was ‘gang leader for a day’ during ethnographic research in a housing project in Chicago. Simon Harding, a criminologist in the UK has published a book on status or ‘weapon dogs’ and another on street gangs in London, in which he describes gang members as players of the game in ‘the casino of life’. Sociologists in the UK who debunked the idea of households where ‘three generations have never worked’ highlighted the almost mythical status of such households amongst politicians, policy-makers, practitioners and members of the public, by likening their research to ‘hunting yetis’. Interest in disadvantaged groups has even led to an emerging literature on ‘over-researched communities’, with some young people in Kings Cross apparently confident in asking researchers working in their neighbourhood about their choice of methodology and ethical approval processes. transitions to adulthood at a time of chastening political attitudes towards young people, and when the local labour market offers only low-paid precarious employment. These are all research studies of individuals and groups living in impoverished areas, but with one eye (at least) on the wider social and structural determinants of the lives of the research participants. In a similar vein, contributors to the recently published book

transitions to adulthood at a time of chastening political attitudes towards young people, and when the local labour market offers only low-paid precarious employment. These are all research studies of individuals and groups living in impoverished areas, but with one eye (at least) on the wider social and structural determinants of the lives of the research participants. In a similar vein, contributors to the recently published book  and their residents are often taken hundreds of miles away, perhaps by people whose only experience or knowledge of poverty might have been gleaned from a carefully managed day trip or two. It is worth remembering that few, if any, of the politicians who voted through, or abstained during, the welfare reforms introduced in the UK since 2010, were going to be substantially affected by them, or could imagine what they might mean to many families already living on low incomes across the country. Numerous researchers have demonstrated various ‘Westminster effects’ on disadvantaged neighbourhoods by highlighting how the government’s recent welfare reforms have had disproportionately greater impact upon poorer areas. Whilst it is vital to acknowledge that where people live can affect their lives, a compelling case can and should be made that the strongest effects exerted on residents of impoverished neighbourhoods often emanate from the words and actions of politicians in Westminster, rather than the allegedly ‘mean streets’ of social housing estates.

and their residents are often taken hundreds of miles away, perhaps by people whose only experience or knowledge of poverty might have been gleaned from a carefully managed day trip or two. It is worth remembering that few, if any, of the politicians who voted through, or abstained during, the welfare reforms introduced in the UK since 2010, were going to be substantially affected by them, or could imagine what they might mean to many families already living on low incomes across the country. Numerous researchers have demonstrated various ‘Westminster effects’ on disadvantaged neighbourhoods by highlighting how the government’s recent welfare reforms have had disproportionately greater impact upon poorer areas. Whilst it is vital to acknowledge that where people live can affect their lives, a compelling case can and should be made that the strongest effects exerted on residents of impoverished neighbourhoods often emanate from the words and actions of politicians in Westminster, rather than the allegedly ‘mean streets’ of social housing estates.

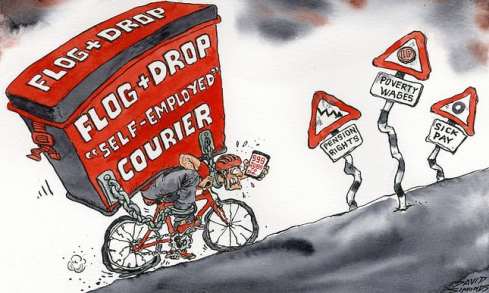

the modern workplace – from call centres, delivery, transport, and care – is not some kind of aberration, but central to the business models of these companies. However, this is no surprise given the constitution of the panel for the review. For example, one was a corporate lawyer who represented businesses in industrial relations disputes, while another had actually invested in Deliveroo! There were no workers’ voices included, nor was the IWGB consulted, despite it successfully organising workers in this sector.

the modern workplace – from call centres, delivery, transport, and care – is not some kind of aberration, but central to the business models of these companies. However, this is no surprise given the constitution of the panel for the review. For example, one was a corporate lawyer who represented businesses in industrial relations disputes, while another had actually invested in Deliveroo! There were no workers’ voices included, nor was the IWGB consulted, despite it successfully organising workers in this sector. make of the working conditions? The rights that workers have fought for – and won – since then are increasingly being eroded by companies, whether through wage theft, misclassification of employment status, or masquerading as platforms rather than employers. Yet, Engels did not see these kinds of deleterious effects as an anomaly, but rather a result of the antagonism between workers and capital.

make of the working conditions? The rights that workers have fought for – and won – since then are increasingly being eroded by companies, whether through wage theft, misclassification of employment status, or masquerading as platforms rather than employers. Yet, Engels did not see these kinds of deleterious effects as an anomaly, but rather a result of the antagonism between workers and capital.

terrorism. And not just paramilitary loyalist terrorism, but also state-sponsored targeting of innocent Catholic civilians, and the assassination of lawyers and other civilian leaders. Its former leader Peter Robinson was arrested and convicted of leading a loyalist mob across the Irish border and attacking an unarmed Garda station in 1986.

terrorism. And not just paramilitary loyalist terrorism, but also state-sponsored targeting of innocent Catholic civilians, and the assassination of lawyers and other civilian leaders. Its former leader Peter Robinson was arrested and convicted of leading a loyalist mob across the Irish border and attacking an unarmed Garda station in 1986. The DUP rhetoric on political violence is pure deflection. Only days before they joined government with Martin McGuinness, they were using the term “Sinn Fein – IRA” and have always condemned terrorism, as the party leader Arlene Foster made clear in her speech. On the other hand, the party is linked closely to the UDA, which is widely seen as it’s preferred paramilitary. As recently as last year the party was channelling £5 million of public money to a UDA slush fund. If you can imagine rural Tories with a soft spot for Combat 18 you might start getting the right idea.

The DUP rhetoric on political violence is pure deflection. Only days before they joined government with Martin McGuinness, they were using the term “Sinn Fein – IRA” and have always condemned terrorism, as the party leader Arlene Foster made clear in her speech. On the other hand, the party is linked closely to the UDA, which is widely seen as it’s preferred paramilitary. As recently as last year the party was channelling £5 million of public money to a UDA slush fund. If you can imagine rural Tories with a soft spot for Combat 18 you might start getting the right idea. clear that the DUP are ready to give backing to Theresa May on a confidence agreement basis, if not a formal coalition. The Tories and their Ulster mutation share enough common ground to allow for a fairly easy relationship to exist. This means we should not rest any hope on the irreconcilability of one reactionary party with another. But neither should we underestimate the rigidity of the DUP – Paisley was famous for saying “No” and “Never” to every UK Prime Minister he met. One sticky issue could be a weakness the left could exploit. And the DUP’s dominance mean that they are charged with representing every unionist in Northern Ireland – a large working class base that will suffer disproportionately from austerity and the Tory attacks. Massive pressure needs to be placed on this weak and wobbly coalition.

clear that the DUP are ready to give backing to Theresa May on a confidence agreement basis, if not a formal coalition. The Tories and their Ulster mutation share enough common ground to allow for a fairly easy relationship to exist. This means we should not rest any hope on the irreconcilability of one reactionary party with another. But neither should we underestimate the rigidity of the DUP – Paisley was famous for saying “No” and “Never” to every UK Prime Minister he met. One sticky issue could be a weakness the left could exploit. And the DUP’s dominance mean that they are charged with representing every unionist in Northern Ireland – a large working class base that will suffer disproportionately from austerity and the Tory attacks. Massive pressure needs to be placed on this weak and wobbly coalition. the anti-gentrification community group ‘Our Brixton’ which fuses art with direct action to support local housing campaigns. I have spent the past two years doing what I can to try and defend my community against the violence that Lambeth Council – a Labour council – inflicts relentlessly on its residents and those who work in the area. I have fought not only on estates, in the streets and at council meetings but I have witnessed also the suffering of friends and neighbours behind closed doors, in their most vulnerable moments.

the anti-gentrification community group ‘Our Brixton’ which fuses art with direct action to support local housing campaigns. I have spent the past two years doing what I can to try and defend my community against the violence that Lambeth Council – a Labour council – inflicts relentlessly on its residents and those who work in the area. I have fought not only on estates, in the streets and at council meetings but I have witnessed also the suffering of friends and neighbours behind closed doors, in their most vulnerable moments.